Recording to Tape: Is it still relevant in 2023? DAWless music making.

Recording to tape was the mainstay of the recording industry for over 40 years, but is tape still relevant in 2023? We look at the pros and cons of tape; the sound, the workflow and discuss whether you should embrace a DAWless analogue workflow…

Recording to Tape – DAWless recording

“Recording to tape”, the phrase alone invokes a response, doesn’t it? If you’re over the age of 40, then memories of tangled tape, head cleaning & alignment and difficult editing are probably still raw. Without a doubt, however, some of the greatest records ever made were recorded entirely on tape.

So, 70 or so years on from the invention of magnetic recording tape, is it still relevant in 2023? Why, when you and I can easily record high-resolution audio with non-linear editing, does tape refuse to die? What is it about recording to tape that still captivates in the digital era?

We’re going to take a deep dive into the qualities of tape we love, as well as those we hate! We’re also going to discuss affordable ways to get some of the same experience of recording to tape. Ready? Let’s dive in…

The Tape Sound

It’s entirely possible that if you’re reading this, you may never have recorded audio to analogue tape before. Whether you’re recording to the humble compact cassette, or on a 2″ 24 track Studer, there are fundamental similarities. Analogue tape responds in an inherently non-linear fashion. Putting that into simple terms, what you put in is not what you get out!

Importantly, tape is a physical medium, and the machines that record to it are based on analogue electronics and mechanical engineering. Variances in the tape stock, the electronics and even the transport can affect the sound coming off the tape itself. If you fancy looking into this more, Nirvana producer Jack Endino made some fascinating experiments on various tape machines.

Recording to tape adds an overall EQ and tonality that is typified by a smooth, rolled-off top-end and a famously “warm” and fat bottom end. As you increase the recording level to tape the signal will progressively transition into harmonic distortion. However, this occurs very gently and progressively, a character which is widely sought after. This “soft-saturation” effect is often very useful for softening transients and smoothing off sources. This effect is most pronounced on sources such as drums and vocals and is also very useful for making distorted electric guitars sound rounder and smoother.

Tape “stock” as it’s known (the actual reels of tape) has always been extremely expensive, however. A reel of 2″ tape costs around $350, and may only give you around 10 minutes (or less) of recording time. Additionally, the machines are finely tuned pieces of engineering. There’s a reason studios would employ someone solely as a “tape op” and it wasn’t just to hit play and record! At the beginning of every session, the machine needs to be cleaned and aligned to tolerances.

Tracking with Tape

One of the things that made tape revolutionary, was the ability to edit recordings. Before this, recordings were cut directly to gramophone records; you had no ability to edit the recording or make a composite “master”.

With that said, it doesn’t mean editing on tape is easy. Tape edits are made by using a razor blade to cut the tape and move sections of your recording around. You then need to physically stick the tape back together again to complete the edit. This is what’s called “destructive editing”; if you place a cut in the wrong place then the recording is irrevocably ruined.

Nonetheless, some astonishing feats of tape editing have been made over the years. Famous pieces of electronic music, such as the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s theme for Dr Who were sequenced and constructed entirely through tape editing and manipulation.

The relative difficulty and risk involved in tape editing, however, pushes you into a different mindset. When it’s difficult to make an edit, you think hard before you do it. Equally, it may be easier to simply re-record until you get a better take. By the same token, you can’t simply click a button and make all the drum hits click to a grid.

It’s this very limitation which presents a workflow that’s very attractive to certain producers. For example, Foo Fighter’s album “Wasting Light” from 2011 was made entirely without computers. In a 2011 interview for Sound on Sound, Butch Vig recounted a conversation with Dave Grohl about the choice to track to tape:

That means you guys have to be razor‑sharp tight. You’ve gotta be so well rehearsed, ’cause I can’t fix anything. I can’t paste drum fills and choruses around. This is gonna be a record about performance, about how you guys play.

Getting the Tape Sound on a Budget

If you’re inspired to experiment with tape and tape workflows, then there’s good news. While the cost of analogue tape stock and vintage machines is extremely high, there are some affordable options! Firstly, it’s still cheap and simple to experiment with cassette tape. and if you fancy playing around with open reel tape, then you can still pick up domestic 1/4″ machines for reasonable money.

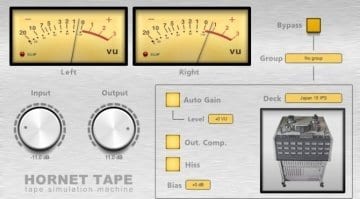

What if all of that is just still too much hassle though? Well, thankfully there are a bunch of plugins nowadays which can give you a taste of the tape sound. Universal Audio’s recreations of the way tape responds are deeply impressive. Ever wondered what your mixes would sound like if they were tracked using a Studer A800? Well then wonder no more! UAD Studer 800 allows you to track and mix with a perfectly modelled, virtual Studer A800.

Equally, Softube offers their imaginatively titled “Tape” plugin which gives you three different characters of tape saturation to play around with. It’s a more pared-down offering compared the UAD plugin, but useful for throwing onto sources to get that saturated tape sound.

Embracing Tape Workflow

What if you’re keen to step away from the overly precise, highly clinical editing of DAW-based workflows though? What if you want to embrace the authenticity of placing performance over-editing? Well, the easiest and cheapest way to do this, is simply to change your own mindset. If you’re working with live performers, then give the session more time and more space. Don’t settle for an “ok” take, thinking you’ll fix it in the edit. Instead strive to get the very, very best performance possible from the get-go. Only then use editing to add the final “pixie dust”.

For example, how many times have you simply copy-pasted an entire chorus section? How about recording that chorus multiple times for some variety? If you’re recording your own band, rather than rely on snapping the rhythm section to a grid, spend more time practising the songs and get tighter playing together. Yes, this all takes time and is one of the reasons why DAWs became so popular. It’s possible to construct a song within a DAW, but it’s much harder to actually capture a great performance.

If the temptation of cut/copy/paste is too great, maybe consider going DAWless for tracking altogether! Products such as the Zoom Livetrack L-20 allow you to record a multitrack performance straight to SD card. If you then need to edit afterwards then the session can be dropped into a DAW. But think of it as a challenge! Put some musicians in a room together and focus on getting the best takes possible, straight to “tape” (oh OK then, SD card!).

Is Tape Still Relevant

In my opinion recording to analogue tape is still relevant today, even if it’s now resigned to niche uses. A similar situation exists in the movie and photography industry regarding film. These traditional, analogue formats carry an inherent aesthetic and workflow which directly influences the finished product. It’s inherently more costly, more time-consuming and ultimately more limiting. For artists with the time and resources, however, the results are often worth the sacrifice.

How about you? Have you had the experience of recording to analogue magnetic tape? Does it intrigue you? Do you feel it’s a valid artistic decision to use tape, or is it something that belongs firmly in the past? Let us know in the comments!

- UAD Studer A800: UAD

- pb: Plugin Boutique

- Softube TAPE: Softube

10 responses to “Recording to Tape: Is it still relevant in 2023? DAWless music making.”

4,2 / 5,0 |

4,2 / 5,0 |

I think the analogy to a film camera is very valid. It can produce beautiful results, is likely not the most practical option in todays world. I’m very glad that larger studios still exist with the tools, but it isn’t something I would typically need as an individual and independent producer. Certainly something cool though.

David Bowie, for the album/song “I’m Afraid of Americans” required every piece of equipment in the chain to be digital. Say you are listening to the radio and a Tom Petty song comes on in analog, and is followed by I’m Afraid of Americans. Are you going to be able to tell the difference if you are not an audio engineer? Will you care? No. It’s the music that matters.

I’ve had the distinct pleasure of recording directly to tape using the old Scully 1/2-in mixdown machine and I believe tape is definitely relevant Loved the article keep them coming Good job

In my view, the sonics of tape belong in the FOMO category. But working with multitracking on a tape recorder is a revelation, with the creative possibilities of tape pitch, using your ears vs eyes, and the restraints of the format as a help rather than limitation. I hope blank cassettes will stay in production!

Back in the cassette 4-track days, I would mix on to HIFI VHS because it uses most of the tape for audio. You can leave the video portion of the tape blank, and as long as you use the shortest speed (120 minutes) it will give you analog recording while retaining lot of dynamic range. That said, a lot of people looking at analog are not looking for a full dynamic range, but something more lofi.

My experience with hardware vs. software in general is that the benefits of hardware have little to do with better sound quality (DSP has gained a lot of ground in the last five years), and more to do with immediacy and commitment.

Modern tape recordings are often made with higher spec hardware than what was available in the golden age, so when they’re not pushed hard they don’t sound significantly different from good digital recordings. But when musicians in the studio know they’re recording to tape and paying by the inch (assuming they don’t have an unlimited budget), it changes the dynamic in the studio in a big way. Musicians tend to be more focused and deliberate, and are willing to look at the big picture more and not sweat the little small stuff.

That, to me, is the real advantage of tape, and analog in general. The convenience and cost effectiveness of digital has its place, but human beings tend to do better creative work when they have more skin in the game. Digital is kind of antithetical to that.

From tape you can learn a lot about bouncing, EQ, how to efficiently record within the contraints of track numbers etc. Trying to get an Abbey Road polish by recording on tape is a waste of time in a home environment, in our view. But using tape, or modern digital 24/32 track recorders/consoles for composition is certainly great for trying something new. It’s not so much that it has to be analogue, but that the method of composition is altered in order to fit the gear. We’ve got a little digital 24 track with CV sync conversion and trigger, and you have to do the drum track right for the whole take, which means you learn how to play the drum machine more efficiently than you would with a far more flexible DAW. There is certainly a place for non-DAW recording, analogue or digital.

Track rhythm section to 1-2” 16 track, bounce straight to a good quality 24/192 converter in pro the DAW. Nirvana!

Roll back to the beginning of the tape if doing punch-ins, use the bounced original as playback to the punch-in point, roll tape enough to settle down, record a new batch of 16 tracks or less.

All the benefits, none of the drawbacks. Plus the gravitas of recording to a really pro wide tape format definitely makes the artist straighten up and fly right. You don’t HAVE to tell them you’ve overcome the editing drawbacks to tape (hand punching in a rhythm section on the master tape is a sphincter tightening event!) and they’ll generally try harder to lock…

At the end of the day, you’ve got a whole slew of 16 track (or whatever you use) chunks easy to cross fade to other bits and you’re back in DAW heaven, just with that 70’s sound.

Great article! Yes, I have lots of experience with recording on Reel to Reel tape… all of it recording myself playing all the instruments (Guitar, Bass, Keyboard/Synth

and Drums) to make it sound like a full band and had excellent results. I did all of this in a closet at my apartment in S.F. on 4 channel machines using AKG 240 headphones for the recording and mixing. I bounced 3 down to 1 channel many times to make it work, always being mindful of tape hiss by increasing the high end slightly while recording, and then lowering it slightly for the bounce. The entire process was silent because I did everything through headphones.

I had nice pedal and rackmount effects to make the instruments sound live like it was in a hall, not in a closet The drums were the only items that used mics in a larger room, which of course could be heard. I started out with a Teac 3340, then a Tascam 22-4 with DBX which allowed more bounces with no hiss. The 22-4 also had a punch in/out pedal so I could make precise corrections, mostly for when I played lead guitar parts. I used only AMPEX 456 tape, which later was made by Quantegy. Years later, I got a Tascam 38 – 8 channel machine with 1/2 inch tape on 10″ reels, and DBX as well. I made many recordings of myself playing all the instruments and sounding like a band, and had friends come over who could sing, as I cannot! It was a great way to make excellent quality recordings. Always keep your heads clean, carefully de-magnetized, and the rubber capstan wheel cleaned and conditioned.

Been recording on tape since I was 10 years old, with a very sophisticated Concertone 1/4 track reversible recording and actual tape echo ! Then recording stereo and 4 track reel to reel recording as a teen aged musician.

Constantly recording live rehearsals on cassettes. Graduated to a 16 track all analog studio with Fostex E-16 then to a very rare Soundcraft Magnetics Division 2 inch 24 track, and finally my fully restored Ampex MM 1100 2 inch 24 track.

I am at a huge advantage because I astonishingly acquired a massive amount of Langevin mic pres and eq’s, that I used with all my studios. But now at this moment I’m accepting the transition to computers.

Thankfully I have 70+ rolls of various aged 2 inch tape, if I really want to record fat drums, bass, acoustic piano or any electric guitar.

Yes I’ll have to bake it.

There’s nothing like 2 inch tape.

A good Studer, Ampex, MCI, 3M, etc would scare the living shit out of any young digital musician. You have to be able to play your instruments and you must be able to perform your music !!!

Tape forces you to get good at the craft of music making.

A properly aligned 2 inch deck, recording at 15 IPS, will give let you record for 30 minutes.

The low end at 15 is like thunder in your fucking lap.

There’s no computer that can get you there.

There’s an American company converting 2 inch decks into 2 inch 8 track recorders.

That’s the last analog frontier.

The Langevin and RCA mic pres are a fine front end for a 24/96 DAW, sure that’s true, but if I had limitless funds, every note would hit tape 1st.

If I was that rich I’d record the best artists I could find for no charge.

Even today great, truly great records are being recorded on 2 inch tape.

I’ll always be grateful for my time with 2 inch tape.

I’ll never bet against tape !

Long Live 2 Inch Tape !